Dr Elsa Urmston: exploring science and art in dance education

News Story

Dance educator and researcher Dr Elsa Urmston co-leads health and wellbeing research at The Place, with a focus on the experiences of implementing periodisation in dance education, and how art and science perspectives can be brought together.

After completing her dance training at the University of Surrey and The Place in the 1990s, Dr Elsa Urmston went onto work in community dance and dance education. She re-joined The Place in 2011 on a freelance basis, to teach subjects related to dance science, pedagogy and supervised undergraduate and postgraduate student dissertations. In 2019, she began to support the implementation of periodisation into the BA degree programme, and she has been working on educational change, curriculum development and research at The Place ever since.

With a research portfolio both at The Place and beyond, Elsa’s research focuses on exploring the health and wellbeing of dancers from a qualitative perspective. She completed her PhD at the University of Exeter on the influence of periodisation on educational change in 2024. She has also been working on a longitudinal project with undergraduate students at The Place since 2019, researching health and wellbeing changes over time. Taking a social science approach to her work, with a focus on qualitative, participatory and creative research methods, Elsa is regularly asked to speak at conferences, and she is currently publishing the findings of her PhD.

The opportunities and tensions of periodisation in dance

Periodisation is a theoretical concept that’s borrowed from sports science, to help dancers pace their training over time,” Elsa explained. “In the long run, we’re trying to reduce the instances of injury, burnout and high levels of stress. We're trying to support students to rest and recover appropriately so they're able to cope with the physical psychological and cognitive load of their education and training.

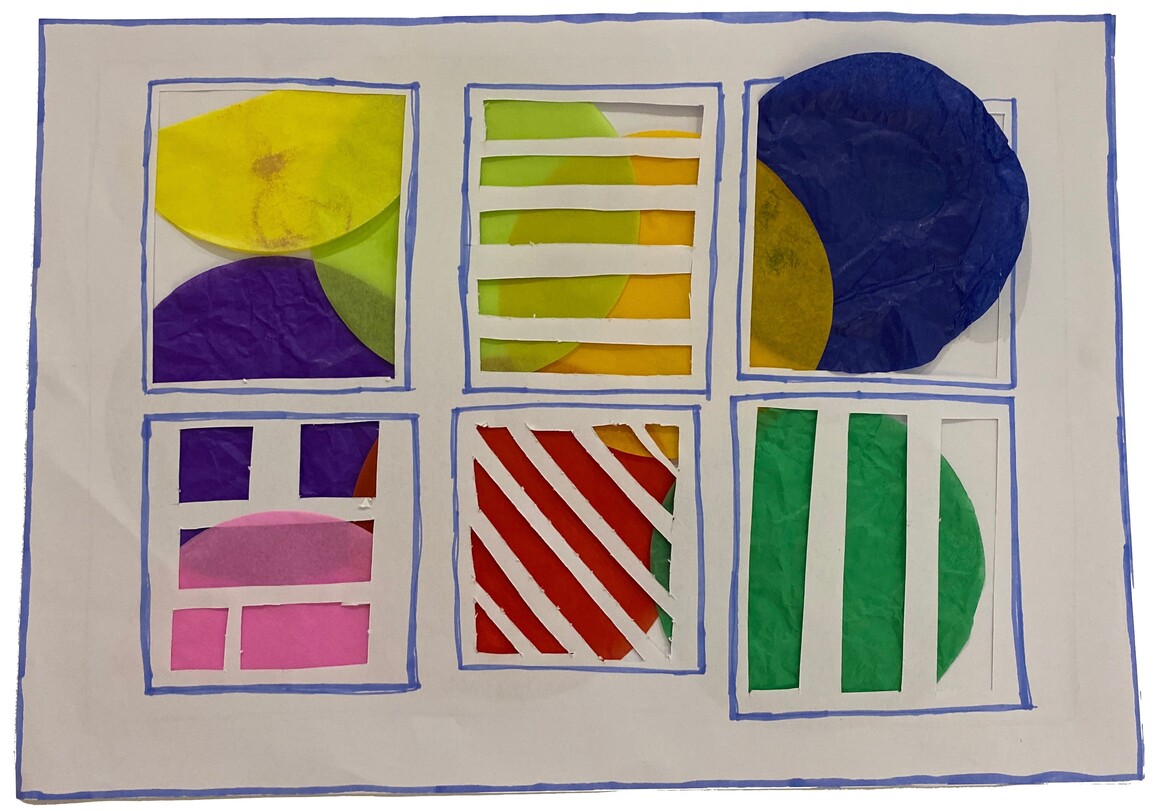

Focusing her PhD on the implementation of periodisation into dance education at The Place, Elsa explored the understanding and experience of the people involved in implementing it, including senior leaders, teachers, artists working with students, and students themselves. Working with a core group of five teachers and five students, plus a wider group of stakeholders, Elsa gathered a range of data and perspectives. She observed the core participants in class, and used footage from fixed cameras and GoPro cameras as discussion points to gain their perspectives on intensity. Participants also kept reflective journals, and used creative methods such as drawing and collages, to log their feelings on training in a periodised context.

The findings of this work cast a light on the complexities of periodisation in dance. It also brought up some aspects that aren’t typically described as part of periodisation in existing literature. “For example, there’s the load associated with coordinating the body,” Elsa said. “If students didn’t have experience in a particular dance style, that would increase the psychological and cognitive load they were facing. But in a theoretical context, you wouldn’t usually see that described as part of what periodisation means to people.”

Elsa’s research also found that teaching to achieve a certain intensity risks perpetuating a didactic teaching style, with the teacher as the leader and central holder of knowledge. Elsa said: “We need to break down the traditional teacher-student hierarchies in dance practice, so this finding suggests that when teaching for physical intensity in dance, we need to support students to think about dance with a somatic attention. The pedagogical power of dancing for intensity should be shifted towards students as much as possible.”

The research also highlighted tensions between science and art in the implementation of periodisation. “There’s a distinction between art-based modes of knowledge and scientific modes of knowledge,” Elsa said. “And there’s a hard-fought place of dance as a way of knowing – and that being a legitimate of understanding the world. There’s a concern that scientific ways of knowing about dance potentially undermines or challenges that. Added to that is a question that is uncomfortable for some people – if we are optimising performance through periodisation to make people more productive and sustained careers – is this contributing to a cycle of neoliberal labour?”

Discovering some of the nuances of the realities of periodisation in dance through this research holds value for continually developing the curriculum at The Place, and for the industry as a whole. “These findings can support more conversations around the tensions, and enable us to find ways to bridge the gaps between what we as artists know and understand to be dance, and what this thing called periodisation is,” Elsa said. “We can better identify where the synergies are, and also what we can leave behind. If something doesn’t work for us as dancers, we’re not going to use it.”

Bringing creativity to dance science

Elsa’s research and research methods have stood out to others as bringing a different perspective to dance science. “My research is qualitative, which in the periodisation research world – both in sport and dance – is pretty rare,” Elsa said. “I'm using creative research methods to find out about something that's scientific in nature. I'm doing education research in dance science, and others seem really intrigued by that.”

Additional strands of research she has in development include looking at how periodisation continues to impact students once they become alumni, and how transition points for students – for example first starting a programme, or returning after university holidays – cause wellbeing to ebb and flow. Understanding qualitatively why and what happens during transition points will help the team understand how to better support students.

This future research will all incorporate participatory and creative research methods that Elsa found to be so effective in her PhD research. “I realised some dancers found it quite difficult to describe or talk about their experiences,” she said. “If you bring activities into a discussion or interview, it gives more focus. Students and teachers I’ve worked with have made a lot of collages. Modelling clay is a real favourite too, particularly when you are asking people to talk about the feeling of something. Because of the tactile nature of modelling clay, there's something in the process of making something that scaffolds the knowledge they have, and helps them explain it both through the artefact they make, and the words they use to describe it.”

Elsa believes The Place is uniquely positioned to do research that can have a positive impact on the dance sector. “There are places that do dance science research, and those that do dance education research,” Elsa said. “The beauty is in these worlds coming together at The Place. There’s a legitimisation of artistic knowledge that The Place brings as an organisation. We can be researching in the studio and doing practice as research. We’re one of only a few institutions to look at the application of dance science research to the context of dance. There are lots of avenues to look at in the crossovers between art and science. I believe we can create a healthy respect for both, and ensure artistic knowledge is really valued within the scientific realm.”