Group conversation with Terry Tsang

Blog post

By Dong Xianliang Yan and Tom Hastings

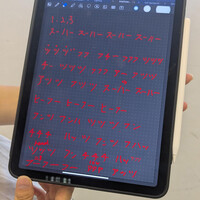

On June 20, Dong Yan initiated a group conversation involving choreographer Terry Tsang, dancers from his current piece, and scholars, including:

Participants:

• Choreographer: Terry TSANG

• Dancers: WANG Xuan (Beijing), CHAI Hedy (Hong Kong), Natalie WONG Ching-tung (Hong Kong), XU Xitong (Hong Kong), Esmee Orgles (London), ZHENG Ti-yun (Taipei), HSIEH Kun-chang (Taipei), LI Jyun-jyun (Taipei)

• Scholars: Dong Yan, Tom Hastings, Dong Shuang, Cheng Yi-fang, Wu Yi-jung, Song Xiaojun, Gao Hailin, and Zhang Shiman

Several scholars observed Terry’s rehearsal process, both with and without the music composition. While we were intrigued throughout, we had not previously had the opportunity to speak directly with the dancers and discuss the creation process. A key question emerged: How did the dancers’ perception and performance evolve over the course of the rehearsal process, especially in relation to the music?

In the first two weeks, Terry informed the dancers that a music composer and programmer would eventually join the project. The music artists prepared materials according to the rehearsal recordings and photos delivered by Terry; however, two of them only became physically involved in the final week. This delay shaped both expectations and uncertainties throughout the rehearsal process.

Across Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Beijing, many dancers have prior experience working with technology in performance. However, most of these engagements were more visual than auditory. For instance, live streaming, projection-based choreography, or motion-capture equipment they encountered always resulted in transforming their bodies into visual representations on other mediums. In contrast, this project placed sound and sonic perception at the core of choreographic development.

The dancers in Terry’s process first encountered sound designers in Studio 7 during early audio experiments. When they later moved to Studio 1 and heard the finalized composition, it prompted a dancer, Kunkun’s new curiosity: What would their movements sound like? What sounds did other dancers generate? How did synchronization, or its absence, affect the sonic and bodily dynamic?

Some dancers initially worked with imagery provided by the choreographer, such as bones and water, and imagined associated sounds internally. However, the final composition offered radically different textures. For instance, a dancer, Ti-yun, noted that what was meant to represent “bone” sounded more like the tearing of muscle, leading them to reimagine their physical expressions based on the sound’s quality. However, one dancer, Xuan, emphasised that music should respond to the body, not the body to the music. She believed that the sounds generated by their bodies, rather than in the opposite way, highlighted the different perspectives regarding the subjective priorities among dancers.

Terry himself reflected that the designers’ sound-making derived from dancers’ bodies were different from what he had originally imagined. Yet, this discrepancy led to deeper insight: rather than the body following the music, music is generated from the body. In my view, Terry suggests that if the body adjusts to the sound, it does not change the fact that the music comes from the body.

During our discussion, British dancer Esmee posed the question, “How do you respond to your partners and the depth of data holistically? How do background sounds shape imagery and presence?” She described how, over time, the dancers developed a deeper mutual awareness (and I quote): “At the beginning, it was hard to move in unison. But through practice, we built a stronger sense of each other, working not just with movement, but with listening and shared imagery.”

Meanwhile, a Hong Kong dancer, Natalie, added that there is a shared space for imagination among dancers. If someone is in or out of that space, dancers can see it. But if they don’t create that space together, if they don’t synchronise through imagination, it can lead to messy, chaotic moments.

Scholar Tom Hastings raised a critical question: “How has the quality of your listening shifted throughout this process? What changed in how you listen through your body?”

Natilie responded that initially, they used a counting machine to understand timing. Then they tried to internalise that rhythm, putting it into their bodies. That created a shared sense of duration. From that base, they started developing more sensation and coordination together.

Terry noted that breath was crucial during their rehearsal. Even before the music artist joined, the dancers used breath to connect. Moving from mechanical counting, to breath, to sensing together was a gradual but essential process.

When asked how the work could develop further, a dancer, Hedy, suggested improving the precision between sound and movement to deepen the audience’s experience of their interrelation. Xuan noted how, in contrast to past performances that used melodic, emotionally appealing music, this piece employed abstract, textured sounds. However, music always functioned as the most dominant and powerful presence, something objective and affecting for both audience and performer.

Terry reflected that many dancers began dancing because music made them feel joy, and it was immediate. But he believes humans are music. Human beings’ postures, experiences, and bodies contain music already. Even without external sound, the music inside the body is the most powerful. As Tom noted later, there’s a nice anecdote about John Cage entering an anechoic chamber (where there is complete silence) and hearing the sound of his heartbeat. So, there is never total silence because the body generates sound.

This naturally led to a wider conversation about the dancer-music relationship. Yifang, a visiting scholar from Taiwan, asked: If dancers are no longer dancing to music, but generate music through motion capture, how does that change the experience? Natilie replied that this approach helped her feel calmer and more in control, not anxious about missing a musical cue. Instead of delivering someone else’s music, she was using her own body to create sound.

Tom followed up: “Historically, music has accompanied dance, advancing narrative or synchronising motion. But now you’re challenging that relationship. We have many ways to describe dancing to music. What vocabulary do we have to describe not dancing to music? Something more dissonant, more separate – how can we articulate the uncoupling of music and movement?”

I draw attention to how, in Chinese, phrases like “聞聲起舞” (dance upon hearing sound) or “應聲而動” (move in response to sound) frame this integral relationship. But what would the vocabulary be for dancing withoutresponding directly to external music?

Hedy recounted that music can support or enhance our imagination. But what if we consider how audiences imagine music? How do they perceive their relationship to our bodies?

Some dancers recalled being surprised in such moments, particularly when Terry deliberately gave up the powerful background music at the end of the performance. Even then, the sound resonated strongly in the dancers’ bodies. As Natalie described it: “In that moment, I could really hear the music, and it connected deeply with my imagination. It also seemed to open a space for the audience—inviting them to think, to connect with what was happening.” In this sense, music becomes another medium through which the audience connects with the performers, not something that must always accompany or align with the dance.

“I think music has many faces,” she said, “and there are many different ways it can be used.” As observers in ArtCross, we find it intriguing to carefully uncover the faces shared by the dancers; it offers an excellent opportunity to form impressions of their masked performance and satisfy our curiosity about how they wear the masks. Even beneath the masks, there are many faces they embody.

Note: this summary focuses on the group discussion regarding acoustic experience; therefore, some discussions with less correlation are not recorded here. We thank everyone who participated in our discussion and contributed their valuable ideas.

Posted by

Andrew Lang