Final presentation

Blog post

By Dong Yan

This reflective essay is revised from my presentation on the final day of ArtsCross, 22 June 2025.

Since its inception in 2009, ArtsCross has served as a significant platform for connecting choreographers, dancers, scholars, and other practitioners. It is not merely a site for presenting artistic works but a space for sustained dialogue and exchange.

Our group, consisting of Tom Hastings, Lynn Wang, Du Le, and myself, focused on the theme of communication for our final presentation, ranging from detailed observations during rehearsals to the ethical and philosophical reflections arising from these processes.

Communication within ArtsCross practically occurs across multiple layers. As scholars, we are often united by a shared curiosity regarding the unfolding of artistic processes. We invested considerable formal and informal time in exchanging ideas, often around specific topics, and these discussions frequently generated new perspectives for all participants. These conversations were documented as notes, subsequently published on the ArtsCross website, contributing to the ongoing archival record of this platform’s history.

However, an important question remains: how can scholars’ insights be conveyed beyond the academic circle and meaningfully engage choreographers and dancers? Typically, scholars’ ideas are presented in a structured form after the final dance performances, marking their first encounter with the artists’ work in a formal setting. Yet the continuous motivation for scholars usually lies in tracing artistic elements from their inception throughout the rehearsal process. For example, one element of shared interest among my colleagues was the “programmer’s table,” a feature visible on the illuminated screen during Terry’s performance. If scholars aim to understand Terry’s practice, they must focus on examining the development of those complex detailed technical programming processes from rehearsal to presentation.

During the first weeks, Terry’s composer developed experimental music remotely by observing and working with the materials recorded by Terry. In many ways, creating music from second-hand materials parallels the work of scholars who engage with existing materials to generate new insights. Throughout this process, both designers and scholars primarily engaged in dialogue with the choreographer, which prompted reflection on my own experiences within the Hong Kong context. There, choreographers often enter projects with a “black box” containing knowledge, tools, and intentions, which are continuously opened and reshaped throughout the creative process. However, elements such as the audio design often remain within the choreographer’s non-transparent black boxes.

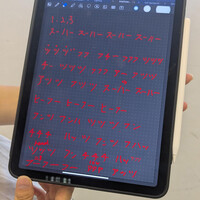

Although ArtsCross actively encourages open dialogue, it is evident that much of the conversation remains between choreographers and dancers or between choreographers and scholars. To broaden this communicative structure, I planned to facilitate a discussion during Terry’s rehearsal that included the choreographer, dancers, and scholars, specifically to explore dancers’ perspectives on the music used in the work. This intervention, which I later emphasized through a hand-drawn illustration, aimed to encourage participants to unpack the “black box” and contribute their ideas, thereby enriching the collective understanding of the creative process. In doing so, it became possible to consider how these conversations influence dancers, choreographers, and scholars alike.

Reviewing my notes from ArtsCross, it became clear that each studio environment differs significantly regarding the transparency of information sharing and scholars’ access to creative processes. Chris reminded me that during the conclusion of ArtsCross 2024 in Taipei, Eddie highlighted the programme’s gradual transition from a professional arts environment to a student-focused training model.

Eddie noted that in professional studios, collaboration with dramaturgs, designers, composers, and rehearsal directors often makes the presence of an external observer less intrusive. I believe our ability to conduct in-depth group discussions within Terry’s rehearsal was closely linked to his status as an independent artist. In Hong Kong’s dance landscape, independent artists frequently seek a diversity of perspectives and feedback, extending beyond the immediate creative team.

However, adapting to contemporary art-making environments, particularly within institutional dance contexts, requires our intervening in the institutional cultures embedded within these practices. Eddie’s observation regarding contemporary creative processes on a global scale differs from the production-oriented approach seen during this edition of ArtsCross.

This leads to a series of questions I wish to pose: What alternative possibilities can ArtsCross explore within its student-focused training model? What essential stages define a meaningful student-centered artistic training environment? How might we cultivate more proactive approaches within the creative process to align participants on a shared understanding of collective artistic creation, particularly with unfamiliar collaborators?

If “professional arts-making” retains its value in cross-cultural contexts, it should enable students to experience artistic practices across different regions while learning how to collaborate with individuals from diverse backgrounds and positions. This is equally essential for involved teacher-choreographers, who must also navigate the dual roles of guiding, collaborating, and experimenting.

In this regard, ArtsCross should be understood not merely as a platform where choreographers work with dancers but as a collective process wherein all participants—including scholars—collaborate to develop new methodologies for addressing shared creative questions. It is this collective inquiry, rather than critique of final performances, that holds the potential to enrich all participants’ understanding of contemporary dance-making practices. At the same time, it raises a critical question about what it truly means to position oneself “at the cutting edge” within these collaborative artistic processes.

Posted by

Andrew Lang