Elements of Play in the ArtsCross Ecosystem 跨藝生態系中的遊戲元素

Blog post

Being one of the key organizers of 2024 ArtsCross Taipei, I have been running around during the three weeks of the event. Therefore, I have not been able to observe the rehearsal process of each dance work regularly. However, I still noticed something interesting throughout the process. Coming from the background of dance education, I will particularly focus on the elements of “play.”

Why play? Play consists of the relational, intersubjective, improvisational, aesthetic and collaborative qualities, which can be observed in early childhood communications (Alcock, 2009). In his classical work of play in culture, Huizinga (1949) argued that play and the arts shares similar qualities. Both are part of cultural phenomena and involve diverse ways of representation, embodiment, meaning making, expression, and communication. The theme of “play” goes together with my ArtsCross colleague Dr. Stefanie Gabriele Sachsenmaier has proposal of ArtsCross as a temporary ecosystem because play also emphasizes on both individuality and inter-connections as does an ecosystem, in which all the organisms or habitants are connected with each other and with the environment.

I will focus on some major elements that are shared by ArtsCross and play, which are the engagement, challenge and boundary breaking, communication and bonding between the choreographers and dancers. And in the end, I will talk about my reflection on the meanings of ArtsCross learning experienc for students in terms of dance education.

1. Engagement:

I found dancers are highly engaged in the rehearsal as if they are performing on stage, especially dancers for LAI Tsei-shuang’s piece, Untitled. I wonder if it is because they became customed to be “watched.” Probablly all the choreographers and dancers had been informed about the presence of the scholars and signed a conscent form, so that they seemed not to be bothered too much. All the scholars just quietly sat against the walls and wrote down what they had seen in the rehearsal quietly. From the articles posted on the weblog of ArtsCross, most observers are pretty open-minded and encouraged and their observation notes are non-judgmental, supportive and cautious.

2. Challenge and Boundary Braking:

Each piece provides different challenges for different dancers, and when a challenge is not overwhelming, it is what makes players feel intrigued and fun. NGUYEN Ngoc Anh’s dance work, To Free or Not to Free, challenged dancers’ habitual body usage by locking the elbows and knees. In addition, I observed that during the rehearsal, the dancers had to work on asymmetrical movement phrases and danced the same movement but with different body parts in pair. For example, when one person circles an arm, the other person circles a leg.

3. Communication:

The choreography process of each work involved a lot of communication, and each dance intends to communicate the choreographer’s ideas about certain issues. In TUNG I-Fen’s work, My Body, My Hisotory--States of Being, all dancers have to talk to a microphone. During the rehearsal, dancers expressed high interests in speaking to a microphone. It seemed that the microphone was like a wane of power. Whoever held the microphone looked empowered and often acted with a sense of playfulness. I-Fen also instructed dancers to play with rhythms, sounds, intonations, or ways of holding the microphone so that the audience would feel they really wanted to say something and they meant it. The rehearsal could turn more adventurous when I-Fen guided the dancers to find ways to speak in any awkward positions or on-going motions. It could develop into a hilarious scene when a dancer is held by other dancers, effortlessly rolling and flipping up and down in the air or over another dancer’s body as if the microphone holder or human carriers were supposed to be invisible.

4. Connectivity/Bonding:

All the choreographers invited dancers to share their personal stories or contribute movement material during the creative process, which created dancers’ personal connections with the dance piece not only mentally but kinesthetically. Alethia Antonia’s piece, Where We Meet, celebrates each individual’s self-identity and cultural root with the element of hip-pop. Her dance piece incorporates a wide variety of movement qualities, including pointing, touching, waving, pausing, squatting (like riding a motor cycle), expanding, rolling, and punching. I found that during the rehearsal, her dancers really enjoyed practicing the movements and showed a sense of achievement with big smiles when they could successfully master the movements. They became particularly motivated when two of them had to face a partner and doing the same movements together. I could always see the dancers’ shiny smile and felt the sense of togetherness and bounding when they kept eye contact to each other to make sure that they could wave their bodies together with their partners and then punch with a sudden joint action at the exact point.

5. Embodiment:

In most dance works, the dancers tried to represent their personal stories through movement and verbal language. All the choreographers have extraordinary abilities to transform daily movements that related to dancers stories into more abstract, aesthetically appealing movements by playing with the elements of Body, Time, Space and Energy. For example, Tsei-shuang played with the qualities of touch and avoiding being touched, I-Fen the quality of sound and speech, Alethia the mixture of hip-pop movements, daily movements, and battle-like but sync duets or trios, and Anh the restriction of body usage. In each dance piece, all the choreographers guided dancers to embody multiple issues of self-identities, the sense of belonging, beauty vs. ugliness, freedom, etc. under the theme of “Body in Motion.”

Reflections:

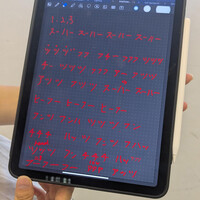

I believe both choreographers and dancers must have learned a lot in the multi-cultural context of ArtsCross. I particularly enjoyed observing dancers’ interactions before or after the rehearsal or when they hanged out aside while the choreographer was working with other dancers. They enjoyed learning practical phrases in another language from each other. But I am more interested in helping my students think about the educational values embedded in their ArtsCross experiences, especially when it is possible for them to become dance teachers some day.

Being a dance teacher educator, I am particularly concerned with the idea that dance learning is more than movement learning. Many of my students are going to teach dance as part of their career, even though they may have a dream of becoming dancers. I am trying to help them understand that when they become teachers in the future, they can create a learning environment that provides engagement, positive challenge, communication, and bonding for their students. I have tried to challenge them to understand that teaching dance is more than just teaching steps or technique. How do they encourage their students to break boundaries? How do they empower themselves, their students and the world by dancing? How can we make dance an essential part of the ecosystem of the world through education? This is what I want to learn by observing how the choreographers worked with dancers in this project.

References:

Alcock, S. (2009). Dressing up play: Rethinking play and playfulness from socio-cultural perspectives. He Kupu, 2(2), 19-30. https://www.hekupu.ac.nz/article/dressing-play-rethinking-play-and-playfulness-socio-cultural-perspectives

Huzinga, J. (1949). Homo ludens: A study of the play element in culture. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Posted by

Yi-jung WU